Here's a roundup of a few comics-related items that crossed my desk recently.

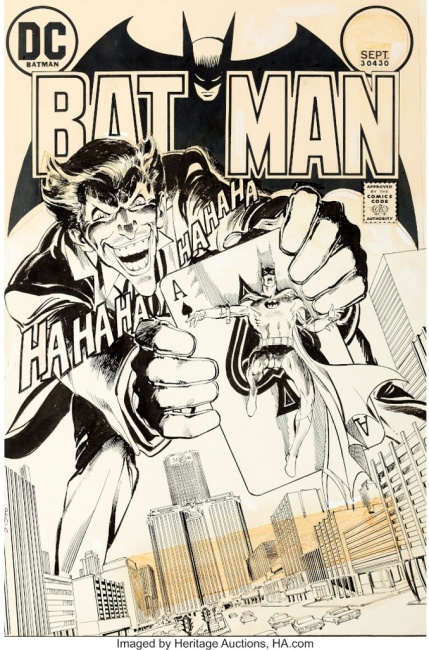

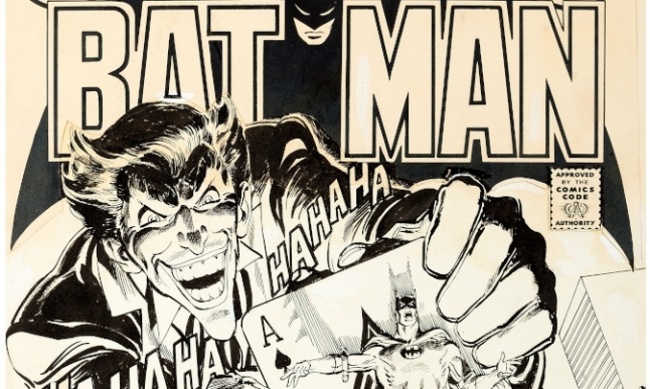

For Art’s Sake. The latest Heritage Auction brought in another round of eye-popping results. The finest known copy of Marvel Comics #1 (CGG 9.4) sold for $1.26 million, a new record for the book (see "Heritage Auction of ‘Marvel Comics’ #1 Realizes a Record Price"). and the original art to Neal Adams’ iconic Batman #251 cover, featuring the return of the Joker as a serious member of Batman’s rogues gallery, hammered at $600K. There was also a six-figure R. Crumb sale, now a routine occurrence, as his "Stoned Again" page from Your Hytone Comix pulled $690,000. Two Jack Kirby/Chic Stone pages from Fantastic Four Annual #2 and the Kirby/Syd Shores cover to Captain America #103 also brought six figures, clearly showing that folks with lots of cash love their Silver and Bronze Age comic art.

The Batman cover got my attention because it’s an interesting comparison to another piece that raised eyebrows a few years back: page 32 of Incredible Hulk #180, featuring the first appearance of Wolverine. That page brought $657,250, which I think remains a record for an ink-on-board panel page, though a couple of covers have gone for more (see "Comic Art Page Sells for $657,250").

In both cases, the pages depict characters who feature prominently in public consciousness beyond the world of comics (Hulk and Wolverine in one case, Batman and Joker in the other). The Batman cover is also by Neal Adams, a significantly more important figure in comic art than either Herb Trimpe or Jack Abel, even if he still lacks the artworld visibility of, say, Frazetta or Crumb. It’s one of Adams’ greatest covers, and it’s a single image, not a panel page. It’s not exactly the debut of the Joker, but the issue does feature the reintroduction of the character as a serious menace, setting the stage for 50 years’ worth of characterization leading to the feature film, which was setting box office records as the hammer was coming down at the Heritage Action.

Based on all that, and especially the opportunity to own a prime Neal Adams Batman cover from his peak era, I figured if anything could knock off the Hulk page, it was this. Alas, not quite. But still an indication that there is a ton of money floating around the top of the economy looking for unusual investment vehicles, and comic art is fitting the bill.

Bad Artists Copy, "Great" Artists Steal. Speaking of art sales, a Simpsons promotional piece by artist Bill Morrison sold earlier this year for a cool $14.8 million in an April auction at Sotheby’s. If you hadn’t heard about this, or are a pal of Bill’s and he didn’t pick up the tab the last time you went to dinner, don’t be upset. It’s because this particular piece was not the original: It was a tracing done by contemporary artist Kaws (Brian Donnelly), and Morrison hasn’t seen a penny for his trouble.

The painting riffs off Morrison’s own riff on the famous cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and was reportedly commissioned by Japanese designer and collector Nigo in 2005. Kaws added two important flourishes to the original: the eyes are replaced by X’s, and Kaws appended his very pricey signature. In most other respects, the composition, linework and color are basically unchanged from the original.

This isn’t the first time this has happened, of course – and that’s the point. There’s an argument to be made that the "appropriation" of "lowbrow" artforms like comics by people in the fine art world represents an important statement on the tyranny of pop culture and commercial imagery in late capitalism. Copyright law recognizes an exception for fair use if the new work transforms the original, including a transformation of context.

Point is, if that’s the statement Kaws wants to make, that’s fine. It’s just not especially original at this late date, since we’re 50 years past Lichtenstein and Warhol, and everything that needs saying about this subject has probably already been said. Bottom line is that he’s an artist, and if this is how he wants to spend his time "creating" work, that’s his right.

In my view, the unindicted culprits in this little boondoggle are the art critics who create a permission structure for collectors to spend that kind of money on, let’s be honest, decorative tracings with little to add to the discourse beyond brand-value bragging rights. Without people championing Kaws and his ilk as radicals and ideologues with something important to contribute to art history – while totally neglecting Morrison and the generations of comic artists who created the "source material" earnestly – no one in their right mind would write that kind of a check. Well, I shouldn’t say that, because there’s always a greater fool somewhere. But it certainly wouldn’t continue to encourage the kind of wholesale theft – excuse me, appropriation – of work that’s legitimate in its own right, to make a tired point that we’ve already heard a dozen times before.

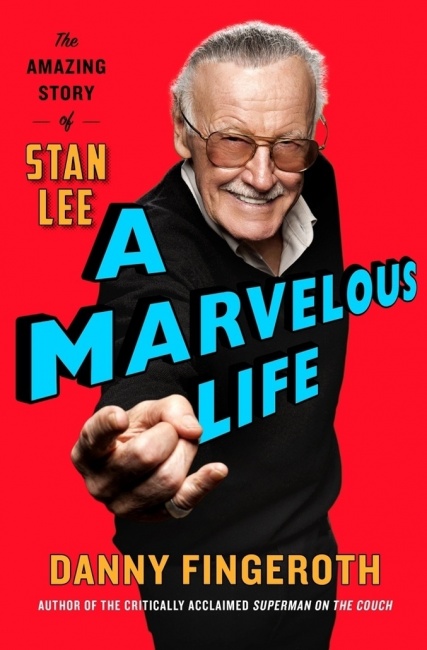

A Marvelous Life. And speaking of people who could increase the value of something just by talking about it in a loud and convincing voice, A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee by Danny Fingeroth just came out earlier this month from St. Martin’s Press (see "’A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee’"). It is, as the title says, a critical biography of Stan the Man, who died this time last year at the age of 95.

Fingeroth, himself a Marvel editor in the 80s and 90s and a frequent interlocutor of Stan’s at Wizard World conventions earlier this decade, brings firsthand expertise to the subject. He’s also a fine writer, at his best rhapsodizing about the impact and importance of Stan Lee’s voice in the letter columns and Bullpen Bulletins, which inarguably created a Marvel brand bigger even than their characters and stories.

Because the question of "who created what" is so fraught, it’s unlikely Fingeroth’s deliberative approach will please everyone, but he lays out the different sides of the question fairly and dispassionately. He keeps his focus on Lee rather than his collaborators, and leaves a fair amount between the lines for readers to judge for themselves.

The book really shines by presenting a picture of Lee as a restless figure struggling to "make it big," whose ambitions always lie just beyond his grasp. Why else step away from Marvel at its (and his) peak and spend decades knocking on doors in Hollywood to a mostly-indifferent response? Even in the final years when everything Lee hoped for was finally getting accomplished – albeit by a company very different from the one he led in the 1960s – he was still driven by insecurity and desire for love and attention.

This is the first of several Stan Lee books ahead in the next year or two. It’s not the conclusive 800-page scholarly work that the subject may warrant, but that’s a feature, not a bug. Worth a look for anyone reading these words.

Finally, a farewell. Last week as I prepared to interview Danny at a book event he was doing here in Seattle, we got word that comics had lost one of its greatest friends and most eloquent voices (see "R.I.P. Tom Spurgeon").

Tom Spurgeon’s contributions to comics scholarship (he co-wrote a book on Stan Lee in 2005, as well as a history of Fantagraphics Books), criticism and community have been amply chronicled here and elsewhere. Speaking for myself, I’ll miss the model of principled, outspoken journalism he represented, and which I, in my very best moments, have tried to haltingly emulate. Seriously, there was no better feeling than seeing something I wrote approvingly referenced in a line or two at Comics Reporter.

I’ll also miss his comradery and warmth. Seeing him was a high point of any occasion in which we happened to be in the same place, which didn’t happen nearly often enough. I’m thankful to have known him, and I think our business is better for his having focused his passion and intellect on making us better. He left us much too soon.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on November 25, 2019 @ 10:45 pm CT

MORE COMICS

From Tiny Onion, Dynamite, Image, IDW

July 18, 2025

There are four Humble Bundle deals running right now, from Tiny Onion, Dynamite, Image, and IDW.

From Marvel Comics

July 18, 2025

Age of Revelation, a new status quo taking place 10 years into the future and arising out of current developments in the X-Men titles, begins in October.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Rob Salkowitz

July 14, 2025

Superman isn't a character who needs a general introduction to the broader public; he just needs an existing global fanbase to take a fresh look.

Column by Scott Thorne

July 14, 2025

This week, columnist Scott Thorne discusses Green Ronin Publishing's GoFundMe to fund its legal fight against Diamond Comic Distributors, and the soft preorders for the latest Horus Heresy box.