Plant needed a moment to process the idea that old comics could sell for the high price of $1. But then he felt an even stronger impulse: He wanted to see what was in that box.

"Holy smokes, I was thrilled," he said.

That was the moment, Plant recalls, that he began his growth from being a Marvel Zombie to being an enthusiast for the wider world of comics. Soon, he was buying and selling at stores he co-owned with friends. Then he started a mail-order business that grew into one of the largest wholesale distributors selling to comic shops.

Along the way, he stuck with his San Jose friends in business, and also broadened his circle to include people like Phil Seuling, the New York convention organizer. The laid back Plant had little in common with the older and gregarious Sueling, but they saw each other as kindred spirits.

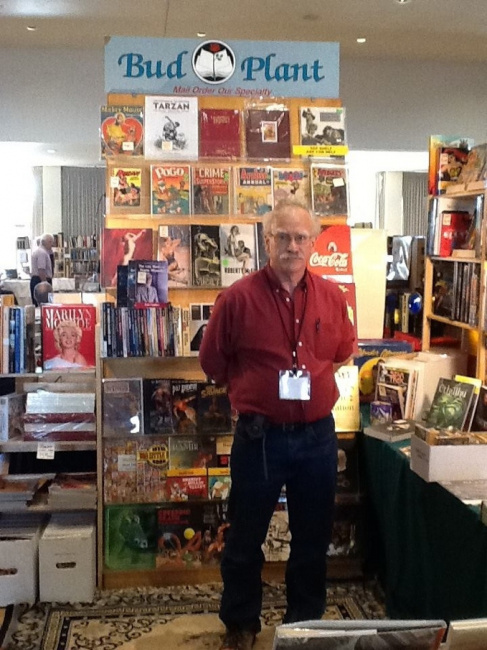

Plant’s life story could double as a history of comics retail and distribution, with special significance for his role in selling underground comics. He shaped key parts of that history, like when he sold his distribution business in 1988 to Steve Geppi and Diamond Comic Distributors, helping to usher in the era of Diamond’s dominance. And he remains in the industry, continuing to operate Bud’s Art Books, a mail order business.

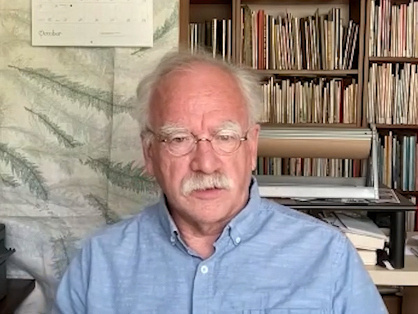

Plant, 71, lives with his partner, Anne Hutchison, an antiquarian bookseller, in Grass Valley, California, a leafy small town at the edge of the Sierra Nevada mountains. He sat for a video interview in Hutchison’s home office, in front of a bookcase filled with inventory to be sold.

To hear Plant tell it, there was no grand plan, just a guy making decisions in the moment. His oldest friends say this self-assessment is very on-brand, but also glosses over the business acumen and easygoing manner that has made him successful.

"He plunged himself into a variety of different endeavors and mastered them all," said Jim Buser, who met Plant when they both were teenagers in San Jose and was a partner with him in several businesses. "You can’t do that without smarts and effort. Bud is likable and honest."

When Francis Plant was a young child in the San Jose area, his family called him "Buddy." In his teen years, this shortened to "Bud."

He used to buy new comics from grocery stores and pharmacies at a time when publishers relied on a network of independent distributors of magazines and newspapers to get their product to market.

To get older comics, he went to places like the used book store with the dollar box, Twice Read Books, and the local flea market.

He befriended other comics enthusiasts and they began to meet at John Barrett’s family’s house. This roomful of people in their teens and early 20s included future retailers and comics historians, including Barrett and Buser, his future business partners.

"My mom had to drive me over there, because I didn't have a license at that point," Plant said. "We all grew up together in this little group, and it was a little microcosm of comic book activity in the San Jose area."

In March of 1968, six of the friends pooled their money and rented a space to open Seven Sons Comic Shop in San Jose. Plant was just 16 and now co-owned a business.

"You'd walk in and it was a funky little place," he said.

"It probably was only maybe 15 feet wide and went back 40 feet," he said. "What we’d do is when things were slow, anybody that wasn't working the counter would be up in the mezzanine playing cards or something."

They sold old comics and science fiction paperbacks.

Less than a year later, the partners sold out to one of the co-owners. Some of them, including Plant, came together again soon after to open a second comic shop, Comic World in San Jose, which lasted for about a year.

Seven Sons and Comic World were two of the earliest comics specialty shops in the country, but the idea of a comic shop wasn’t fully formed. Plant’s first two stores didn’t sell new comics, and to a customer they probably didn’t seem very different from the comics selections at used book stores.

The San Jose friends took a break from retailing but they still bought and sold comics and began making trips to some of the early comics conventions.

In 1970, they drove to New York where they were going to attend the Comic Art Convention. It was the largest event of its type in the country, put on by Phil Seuling, a high school English teacher who had side businesses in comics.

The van from San Jose pulled into Brooklyn late at night, a day ahead of schedule, and they parked outside of Seuling’s building. They walked up many flights of stairs to his apartment and knocked.

Seuling greeted them in a T-shirt and briefs. He was annoyed for a moment, but warmed up once he realized it was "the California guys." He cleared spots on the floor for the visitors to unroll their sleeping bags.

At the convention in Manhattan, Plant and his friends worked security and also shopped and traded comics. They had found a much larger world, in which some of the people who sell comics are friends with top comics creators.

Plant had been taking business classes at San Jose State University, and he started to sell comics through mail order. He found that there was demand for underground comics, the adults-only comics coming out of San Francisco and other places.

"Underground comics blossomed, starting in ’69, ’70, ’71," he said. "Boom, all of a sudden, it was all kinds of fun underground comics. Some of them were total junk. Some of them were very good."

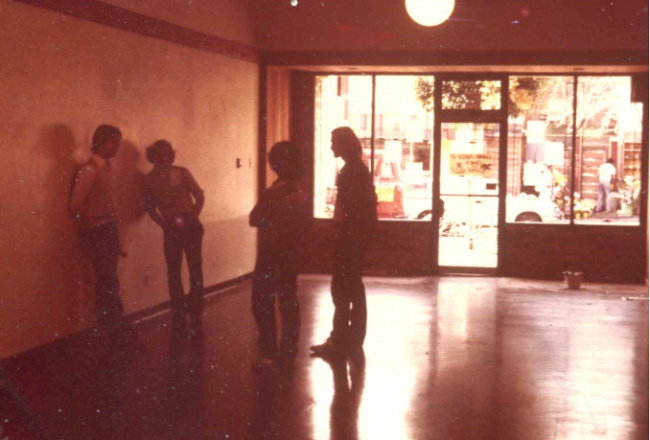

Checking out the second location for the Telegraph Avenue Comics & Comix; L to r Scott Maple, Plant, John Barrett, Jim Buser

In 1973, Seuling and Jonni Levas, his business partner and girlfriend, made agreements with mainstream comics publishers to be able to sell directly to comic shops. Instead of going through the middleman of news distributors, Seuling and Levas could take orders from shops and obtain comics straight from the printer. Shops could order specific quantities of titles and be confident that they were going to arrive in sellable condition, neither of which was true before.

Comics from news distributors were returnable if unsold, and carried a tiny profit margin, while the products from Seuling and Levas were be nonreturnable, which suited the collectable nature of comics, and had a larger margin.

This new business, later called Sea Gate Distributors, helped to transform comics retail.

Comics & Comix had been buying new comics from a news distributor, but soon switched to buying from Sea Gate.

The rise of Sea Gate also affected Plant’s mail-order business. The existence of a "direct market," as it came to be called (see "Why Is It Called the Direct Market?"), for new comics helped to identify the retailers who also might be customers for the comics and other material that Plant was selling.

Seuling and Plant worked together through their businesses to support comics and fanzines that they wanted to see succeed, agreeing to buy large numbers of copies and resell the publications. Examples include The Comics Journal and Elfquest.

Plant also published or co-published selected comics, like The First Kingdom, Jack Katz’s sci-fi epic.

But Plant wasn’t yet a distributor of DC, Marvel and other mainstream comics—at least not yet.

His shift to become a major distributor came almost by accident. Seuling and Levas lost their near monopoly of mainstream comics distribution in the late-1970s in a series of legal settlements. The dominance of Sea Gate was replaced with competition among many distributors.

Charles Abar, a distributor in Northern California, had a business selling comics along with packaging products for collectibles, and he wanted to get out of comics. He asked Plant to buy this side of the business and Plant agreed, inheriting a list of customers in California in 1982.

Then, in 1984, Pacific Comics was going out of business and owed Plant money. To make things right, Pacific’s co-owner, Bill Schanes, offered to transfer ownership of Pacific’s California warehouses and distribution business.

Bud Plant Inc. was soon the leading comics distributor in the Western United States.

But the company’s owner and namesake wasn’t enjoying this at all. He was uncomfortable with the high risks and low margins of the business. He also faced tough competition from Capital City Distribution of Wisconsin, which was the largest distributor in the country and was making an aggressive play in California.

Plant wanted to sell his business, and it was a pretty easy decision who to sell to. Schanes, an old friend, was now a top executive for Diamond Comics Distributors in Baltimore, a major distributor that was looking to expand into a national player.

"He treated me right when Pacific went down," Plant said. "He was a real straight shooter, a real good guy. I said, ‘This is a guy I can talk to.’"

Plant made a deal in 1988 to sell to Diamond and its owner, Steve Geppi. With that agreement, Diamond leapfrogged Capital City to become the largest comics distributor in the country. Diamond was well-positioned to survive in the market chaos to come, a period that would end with Diamond as the sole surviving distributor and a near-monopoly.

As the 1990s began, Plant was back to focusing on a small mail-order business, which he had kept in the sale to Diamond.

Plant’s career is notable as much for what he has sold as it is for the heights he reached. He sold underground comics, fanzines, foreign comics, art portfolios and art books, providing those products to individuals and stores.

"He offered more than just comic books," said Greg Ketter, co-owner of Dreamhaven Books & Comics in Minneapolis, who has been buying from Plant almost as long as Plant has been in business. "I felt there was more to being a good comics retailer than just offering the same comic books as everyone else and Bud was very helpful in that regard. He led me to many great books and comics."

While Seuling was essential for bringing new mainstream comics into comic shops, Plant was the person who had the cool and weird stuff. He did this without calling attention to himself.

"Bud’s never sought out publicity, and he’s not a glad-hander," said Mike Friedrich, the comics writer and independent publishing pioneer, in a 2015 interview. The two have known each other since the early 1970s in the Bay Area comics scene.

Plant continues to operate Bud’s Art Books, his mail-order business, and is one of the few people from his generation who is still selling comics as a full-time job. Many of his contemporaries, like John Barrett and Phil Seuling, have died.

But Plant has reduced his workload. He stopped exhibiting at Comic-Con International in San Diego in 2018, a decision that got attention in the industry because he was one of the exhibitors at the first edition of the con in 1970 and had been there ever since (see "Bud Plant Ends 48-Year Run").

He goes to his warehouse and office in Grass Valley three days a week, and works from home the rest of the time.

He doesn’t know when he will sell or close the business. He was going to shut it down in 2011, but the going-out-of-business sale was so successful that he decided to keep it going.

Whenever he decides to step away, he will miss his warehouse, the rows of metal shelves stacked with books going back decades, and his second-floor office, overflowing with comics and papers would be at home in a university archive.

His legacy is all around him, but don’t expect him to talk in such terms.

"I don’t sit back and think about the last 50 years," he said. "I'm concentrating day to day on getting things done."

For this article, writer Dan Gearino (author of The Comic Shop, see "New Edition of ‘Comic Shop’") conducted a meaty video interview with Plant, which you can watch in three parts:

- In Part 1, Plant talks about the very early days of the comics business in the 1960s, and some of the first comic stores in California.

- In Part 2, he talks about meeting Phil Seuling, the beginnings of the direct market, and opening the first Comics & Comix store.

- In Part 3, he talks about rapid growth in the 1980s, selling his wholesale business to Diamond, and the meaning of it all.

We are also making available full transcripts of the interview, in three parts corresponding to the three parts of the video interview.

ICv2 Interview Transcript: Bud Plant Part 1

ICv2 Interview Transcript: Bud Plant Part 2

ICv2 Interview Transcript: Bud Plant Part 3