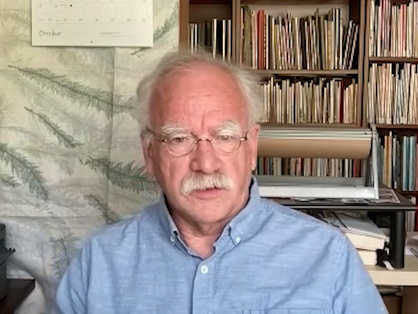

For his article on direct market pioneer Bud Plant (see "Bud Plant, a Pioneer"), Dan Gearino (author of The Comic Shop, see "New Edition of ‘Comic Shop’") conducted a meaty video interview with Plant, which you can watch in three parts:

Bud Plant Video Interview, Part 1

Bud Plant Video Interview, Part 2

Bud Plant Video Interview, Part 3

We are also making available full transcripts of the interview, in three parts corresponding to the three parts of the video interview. In Part 3, Plant talks about rapid growth in the 1980s, selling his wholesale business to Diamond, and his ongoing ecommerce business. In Part 1, he talked about the very early days of the comics business in the 1960s, and some of the first comic stores in California. In Part 2, he talked about meeting Phil Seuling, the beginnings of the direct market, and opening the first Comics & Comix store.

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

This distribution side of your business, when did it really level up? Because you would eventually be doing the Code Comics or the Marvel and DC as well, but walk me through the major steps on that path?

Basically, from, let's call it, the early '70s through about 1981, I was doing the retail mail order to customers, but I was also doing a certain amount of wholesale and it was just all sandwiched in together. There wasn't separate entities that or anything. By that time, Phil Seuling has established the direct market. He's bringing in new comics and my stores, Comics & Comix are buying new comics from Phil. This would be the late '70s. My partner, John, really wanted me to become a comic distributor because, in his eyes, he'd be getting cheaper comics. [laughs] If I was a distributor, I'd be passing all that on to him at my cost. John, like any businessman, he wants to get a better deal, better discount on stuff.

I resisted for a long time because I liked what I was dealing with the books and the fanzines and even the undergrounds. I felt like that was enough. But I finally gave in. One of the distributors in San Jose, a small distributor called Charles Abar (again, just a guy's name, Charles Abar), but he was distributing comics early on and he also had a full‑time regular job. He was a delivery guy for the San Francisco Chronicle. His wife gave him an ultimatum and said, "You're never here because you're always running one business or the other. You got to figure out what you're going to do." So Charles came to me and said, "I'll sell you the distribution business." He already had accounts.

At this point, Phil Seuling was no longer the exclusive distributor. This is after the whole thing where he lost the exclusivity because of the lawsuit from New Media/Irjax. It opened up the whole world of other people getting in and dealing directly with Marvel and with DC and with Charlton.

Charles already had accounts with those guys. I just stepped in, took over his accounts, and started distributing comics. I started running a route, which is another unpleasant thing. We had to get the comics delivered in Grass Valley, then shove them all into a van as fast as we could, and get them down to comic book shops. We were hand delivering to the comic book shops all the way down into San Jose. It was a horrible route. It took 14 hours of driving or something, and we're delivering all this stuff for free. That would have been '80, '81, or very early '82, where I got pulled into distributing comics. Then the whole distribution thing really took over and became a huge part of my business. By '88, my retail businesses still existed. I was doing comic catalogs and everything, but it had gotten very small in comparison to the wholesale part of it.

The wholesale part and the mainstream comics distribution. Were you growing through acquisition or were you just adding accounts?

It was both, but the acquisition was a big part of it, too. When Pacific Comics went bankrupt, that was my first big acquisition. At that point, I'm always bad on these years, but Pacific went down in '84 maybe. Let's call it '84, something like that.

At the time, DC only dealt with a few distributors. They didn't want to deal with everybody. They just wanted to have this little group that they could really work with, meet with them once a year, and sell their products. So we had what we called sub‑distributors.

I was a regular DC distributor, but I sub‑distributed to Pacific Comics and to three or four other outfits. Pacific Comics basically ran up a debt with me. They go bankrupt. Bill Schanes calls me up and says, "We don't have any money. We're going bankrupt." Bill Schanes is a really straight‑shooting guy. He worked for Diamond later on. He's the reason I sold out to Diamond. Bill said, "I'll give you the business." He owed me 26,000 bucks, but that was in '84. That was a lot of money. A lot of money for a small business, too. He handed me the business. He said, "I've got a warehouse in LA. I've got a manager that you can stick in." I went down there and he introduced me to everybody and gave me those accounts and boom, all of a sudden I had distribution in Southern California.

That would've been my third warehouse. I had a warehouse in Grass Valley. Then I'd opened up another one in the San Francisco area, and then all of a sudden I had this one in Los Angeles, and pretty quickly we opened up another one in San Diego. That's four warehouses at that point.

Then Mile High. Same thing happened with Mile High, except they owed me a lot more money. They were the sub‑distributor. I was selling them DCs and they went down. I call it Mile High, but it was technically Alternate Realities. Chuck’s wife, Nanette owned Alternate Realities and they went down owing me a bunch of money, so the same thing, Chuck hands me his warehouse and his staff in Denver. He had another warehouse in St. Louis at the airport, so he could ship comics out by air.

It went from Sparta to St. Louis Airport, and then fly out. All of a sudden, I acquired two more warehouses. Although, that's basically at the end of my distribution era. I acquired those at the same time I was trying to sell out to Geppi late '87 or early '88.

You didn't plan on becoming some distribution kingpin, did you?

[laughs] No.

It sounds like you just stumbled into it, right?

Yeah. It was really organic. I just kept doing what seemed to make sense at the time. I kept hiring more people and opening more warehouses. We opened a warehouse in Phoenix, Arizona, because we were starting to think, "Where else can we open up a new warehouse? There's distributors all over the place." Diamond had their places. Capital City had warehouses.

Capital City and us, we were competing against each other in the San Francisco area and also in the Los Angeles area. I opened up a warehouse in Phoenix, which has never ever made money, but it seemed like, "That's a big, metropolitan area, why not?" It was purely organic. I didn't have a master plan or anything. It just kept growing.

You were ready to get out of distributing. This business has gotten much bigger and probably much more headache than you ever had planned.

Yeah.

It's time to sell. In hindsight, that sale was a pretty consequential event in terms of what happens with the market after that. What was your thought process? How did you end up making the decision that you made?

I was actually in pretty deep financial straits. In late '87, '88, I was selling to a lot of sub‑distributors, like I mentioned, so I had really big accounts and operating on really small margins because it was really competitive in those days. There was a lot of distributors. We were buying comics at 60% off, 62% off, and turning them around and selling to people at 55% off, 56% off.

We were operating at a very tiny margin. If you lose an account, you really take it in the shorts because you weren't making that much money anyway, and all of a sudden, you lose an account. A guy goes down for owing you $10,000 or $20,000, or $30,000. You've lost a lot of money because you paid real money for those comics and your margin was tiny.

Those early comic shops were not being run by real businessmen. They were being run by fans like we were, and a lot of these guys didn't have the privilege of starting as small as I did and learning as they go. Of course, I also went to college and got a little business education, too. Even Comics & Comix was in deep trouble at that point. We just had overexpanded. We were piling up inventory. Comic book prices were going up really fast. It was really easy to tie up a lot of money in inventory that wasn't selling. A lot of comic book shops were getting themselves in trouble doing that.

I was suffering from that because I was giving all these guys credit. All of a sudden, maybe they’d owe me this, and this, and this, and I had a lot of bad debt piling up. Anyway, I was in financial difficulties. I also was not having a lot of fun being a distributor. It was a lot of business to deal with. I had seven warehouses at that point.

Still, I liked the retail business. I got more enjoyment out of the retail business, out of carrying books and the other products rather than carrying the latest Wonder Woman and Spider-Man and Fantastic Four, and all that stuff. It was kind of exciting, but boy, it was a lot of work. Anyway, I just had a choice of who to sell to, and Bill Schanes had gone to work for Steve Geppi at Diamond. Like I say, Bill Schanes, he treated me right when Pacific went down. He was a real straight shooter, a real good guy. I said this is a guy I can talk to.

You had to be careful because there was so much competition in the distribution business in those days. You didn't want your accounts to know that you might be selling out because your competitors could come along, and say, "You know, you may not get your comics next week, because Bud's going to sell out, or Bud's going to go out of business. You better switch over and start buying it from us." So accounts would switch over a lot. A lot of times, they’d switch over, and end up leaving their old distributor with a big debt. "Oh, well. We'll try to pay it off." It was a lack of capital in the business, I guess that's the bottom line, and a lot of amateur businessmen.

Anyway, I'm in financial difficulties and I think it's time to get out and it's like, "Can I get out and get away with my shirt on my back, and not jeopardize all the business that I built up for so long?" So I make a deal with Geppi and sell the distribution business to him. I folded off the retail business. It was still going on. I'm still doing the catalogs. We had six employees entirely devoted to that. We went off and started doing retail again and then rebuilt that business just on retail.

To what extent were you conscious of how your selling to Diamond would be a pretty major shift in the competitive balance of the market?

There was no way to be conscious of that at the time. I didn't know that Marvel was suddenly going to yank their distribution away from the distributors and try to do their own thing.

I knew that I was the third‑largest distributor. Geppi was second largest. Capital was first largest. We were all within a certain range of each other. I pushed Geppi over into being the largest distributor.

How much that affected the history of distribution? We'll never know. If I had sold out to Capital City? I don't know. Would Capital City be the Diamond of today? Maybe, maybe not, don't know.

Capital City was the more hip, innovative distributor, to be honest, at that time. Geppi really needed what he got from my business, which was catalog production, and selling non‑comics‑related stuff, the book distribution, he got my employees and stuff, so he got a lot out of it. It was a good blending of the two businesses.

Capital was already doing a better job, honestly, but I had a better relationship with Geppi. I had no idea what was going to happen, [that] all the distributors were going to [laughs] disappear in the next, what, five years, or something.

When Capital had been a direct competitor, you guys were clawing for accounts. You guys, it was pretty up‑in‑your‑face competition. That was not the case with Diamond. Diamond was a regional player, not in your region, right?

Exactly. Diamond was strictly back East, so there was no real competition between the two of us. He had enough to deal with on the East Coast. He had his own sub‑distributors and stuff, but he had enough to deal with, whereas Capital was all over the place. Like I say, we were competing with Capital in two locations in California. There was a lot of competition. We were all friendly. We had a distributor organization (I was the president at one time) called IADD, and we got together as distributors and tried to figure out how to get better discounts from publishers and how to improve conditions in the comics field. We were all also out there trying to [laughs] (our managers, rather) trying to get accounts. Trying to do a better job than those guys are doing for you, or something.

After you've sold the distribution business, of course, a lot's happened since then, but you entered this phase where you're still in Grass Valley. You're doing the mail‑order business. We enter this era, for you, anyway, that continues all the way to today, right? Or is that a gross simplification of how you view that period?

Yeah, with some bumps along the way. I'm still doing the same thing. Basically, what I call the salad years, from the time I sold out as we regrew the business there were some really good years there. I was carrying all this, everything related to comics, but not comics themselves.I'm advertising in Overstreet. I'm advertising in the back covers of Savage Sword of Conan. Getting a lot of publicity that way, cranking out catalogs, going to shows still. The business grew really well. We were up to 26 employees at one time.

We had a non‑competition agreement with Diamond, so for 10 years I didn't do any wholesale. I edged back into wholesale after that a little bit, but I didn't have enough to really offer to people since I wasn't handling new comics and all the new product, that kind of product. It was hard. I was a sort of a subsidiary source for material.

Also, it would be tough because if something got popular, a bookstore or a dealer might want five or ten copies, and all of a sudden I had no copies for my retail customers. It was hard to balance that. I finally just said I'm going to stick to straight retail, do the best I can with my retail customers, and not take away with this liberal wholesale thing that wasn't necessarily that profitable.

Anyway, we did really well. Then starting in about 2008, things got grim with the 2008 recession. I was happily selling everything at that point at full retail price. Discounting started happening. People started buying less material. Amazon comes along, starts discounting stuff like crazy.

From 2008 to 2011, profit‑wise, the business was heading downhill. I tried to sell it. Eclipse was interested in it at one time, IDW was interested, but I couldn't really pull off anything selling it, so I finally gave up and said, "I'm going to shut it down because I can't keep losing money." I’d lost quite a bit in the last four years or so. I stopped taking a salary. I went on a sabbatical for a while and just took some time off.

I was going to shut the business down and we put out our last catalog with a big thing in the catalog: “This is it. This is the last catalog. We're discounting everything. This is your last chance.” It did great. We sold loads and loads of stuff. It was really popular. Everybody said, "Oh my God, I better get that book. I've been thinking about from Bud." All we did was fill orders for two or three months. It was just incredible.

But then we said, "You know what, maybe we can do it without the catalogs for a while, and we sort of edged our way back into it. Then business regrew. Basically starting in 2012, we were down to three people. Then we regrew the business again. That's where it is now. That was the little bump in the road.

Today, how many employees do you have?

My payroll's seven, eight people. I've got some people like, LaDonna has worked for me for 32, 33 years. She was back in the old days and she moved forward with me. Then some other people back in the old days, they went off and did other things and then they came back and started working for me again. I've got a lot of veteran folks now.

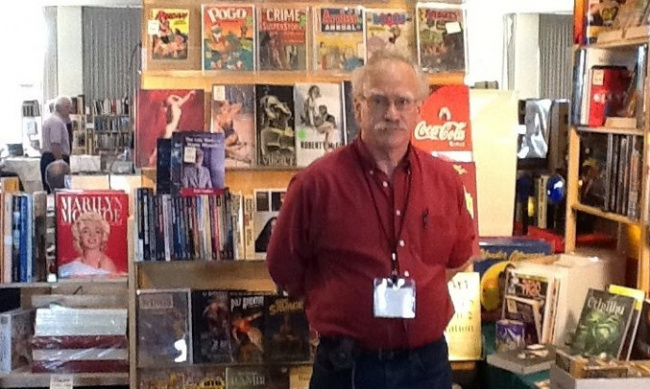

You do any shows anymore?

Just a tiny bit. There's a Vintage Comics Berkeley show that I do a couple times a year that I like and I do OAFCon in Oklahoma City. That's a kind of a fanboy vintage show. That's really fun. I really enjoy that. I've known all those guys. Those are the guys from 1969, 1970 that I first met. They're still there except for the poor guys that have died now. We all get together and do that show.

Other than that, what I do is antiquarian books shows because I've got this whole second business with my partner Anne, where we sell antiquarian books, old illustrated books, and children's books. I enjoy the antiquarian books shows a little better than the comic book shows. Comic book shows, they've changed. They're oriented towards newer material and newer artists that I don't know as well. I like the vintage book shows. They're less stress, much less stress than doing San Diego.

How many of those shows do you do in a year?

Let's see, one, two, three, four. We probably do about a half dozen a year or so. There's a couple Sacramento shows. There's a Seattle, Portland, and then the big ABAA show that's either in Oakland or San Francisco or LA. They alternate back and forth.

Besides comic books, I collect all that stuff. All this stuff you can see in back of me. Although this is Anne's stock, this is Anne's children books stock here. I collect old illustrated books and old stuff going back into the 1800s. I'm hardcore addicted to collecting, hopefully, it won't be buried with me.

When you have people with just giant collections, and I know that, I've talked about this with you, but then also just some of your friends, it's like just with your life in comics, you've just got so much stuff. What do you do with all that? Are your kids going to just be like, "OK, guys, figure it out."? Or...?

I haven't figured it out. My parents were pretty long‑lived. I'm hoping I've still got another 20, 25 years, so I figure, "I don't have to make that decision for a while." Actually, what's happening now is that yet another thing that's come along. My old buddies that were older than me or not as healthy. They're passing away.

I've been ending up with collections that way. I'm selling a collection, a comics collection right now for Ken Sanders Cosmic Aeroplane. He's in the antiquarian book business and doesn't know comics as well. I'm buying parts of his collection and selling the rest of it for him.

I've had another guy, a good friend that passed away in Sacramento and I handled his collection, and another really good friend in Portland, he was older than I was, he passed away. Huge collection. 500 boxes, 500 banker boxes of illustrated books, and some comics. I've been working with that. That’s yet demand on my time, so I don't have time to be thinking about selling my personal collection because I got all this other stuff to deal with first.

I remember, probably the first time we talked I asked you, how much longer do you think you'll do this? What was that? At least five years ago? More than that. In five years from now, do you think I'll still get that email every Thursday from Buds Art books? Or what do you...?

That's a good question. I'm just about to turn 71 and I'm thinking I'm on this five‑year plan that keeps moving forward, but I'm thinking, yeah, in five years, I'm 75, 76. I'd like to be maybe out of the new‑book business with the eight employees and stuff. I'm only working three days a week now. That's no complaint, although, while I'm at home, I'm still doing a lot of proofing and doing a lot of stuff here. That's a much nicer schedule. Still, I'm doing parts of the job that I don't enjoy that much. There's endless Marvel graphic novels and DC stuff, and everything. Some of it's very nice. Some of it's just another book that we carry.

In my ideal world, I could find somebody to buy the business in the next five years and turn it over to them and have them continue it. I hope that I can pull that off. I haven't really actively gone after anybody yet, but that's my goal. If I can't, I'll have to do the same thing I did back in 2011, which is, put out a final catalog really this time, closeout, and maybe sell all this stuff off. Do the best I can.

Do you still write the capsule summaries in the catalog?

Yes and no. We take what a publisher gives us. I can't take credit for all that. I take what a publisher gives us and then I adapt it. Sometimes I may go with mostly what they say, and sometimes I may add my own spin on it and my recommendation and stuff like that. I don't write them from scratch, no, but I edit them and adapt them.

I know from talking to Chuck Rozanski who was of your generation. He talks about the joy of walking the warehouse and just seeing all those books. There's just something. I remember, when I was in your warehouse, there is this Willy Wonka factory quality of just seeing all of those books. I remember walking through there with you and you pick up a Carl Barks book, and I remember you're pointing it out how Barks always ends every page on a cliffhanger. Then there's the Al Williamson EC collection, and then there's...

If I imagine what it must be like for you thinking about your future, it would be hard not going into that every day or the days that you work or maybe not. Maybe you've done it. It's really cool for me to be there for a few hours one day, but how do you feel just still being able to go in and walk those aisles?

I don't walk the aisles as much as I used to. [laughs] I get the stack of new items and I'm sitting there picking out the scans for them and writing descriptions. Of course, I choose all the new items that we carry still. Nobody else does that. It's tough. I've been doing it for—it's 53 years I've been running just the mail‑order business.

It's hard to know how it's going to feel. It really is. Stuff comes in and books come in and I'm really excited about them and they're really great. Then other stuff comes in and I'm not so excited. That's the downside of it.

And there’s the whole employee thing. I've got some wonderful employees. There's always a weak person or two. We had a wonderful girl who was packing for us. She was an alcoholic. We had to let her go. We really loved her, but she just had an alcoholic problem. That kind of stuff, I don't relish dealing with. I try to get somebody else to handle it because I used to have a manager when we were big that handled all the employees and I could just do my marketing thing. As much as I can, I still do that. I've got a couple of people that are supervisors that handle the folks.

Still, there's all that business stuff. When we got the big snowfall recently, the business was closed for five days. That's stressful because I've got bills to pay and I got no electricity at the warehouse, so I can't fill orders. That was no fun.

There's downsides to it. I'm still really excited about the good stuff, but it's been 53 years. I could pack it up at some point. I'd still be very actively in the old books, the antiquarian books. I could still be selling comic book collections and playing with those. I'd have plenty to keep me occupied.

The last thing I wanted to ask you was just about the direct market. If we regard that Phil Seuling moment in 1973 where he makes these deals with the major publishers, if we regard that as the beginning of the direct market, and I think that's probably the most broadly agreed upon—if you have to pick, this is where it started, that's it. We've now had the direct market for 50 years. You've seen it all, all the ups and downs. You remember comics before the direct market. If you were writing the history of the direct market, what was the significance of the creation of this thing in 1973?

To a certain extent, it probably saved, it saved comics somewhat. Comics might have survived, but I think the direct market really came along at the right time. Comics were having a hard time in the early '70s.

Distributors were having less and less interest in them. The traditional distributors had less and less interest in them, because the profit margin is very small. The old argument was they could make a lot more money off of a magazine like Playboy than they do off a comic.

Of course, also, the stores, comic stores, if they were dealing with the distributor like in our early days, they couldn't get what they wanted. Seuling changed all that. Comic stores could now cater to the clientele. They normally kept the comic publishers going, but they expanded and expanded. Of course, they expanded too much, and they contracted in the late '80s and early '90s. There used to be a lot more comic book shops.

Everything's adapted. Everything's changed now. Comic books are a lot more expensive. They aren't necessarily out there in front of little kids—8, 9, 10, 11‑year‑olds—unless they go into a comic shop. It has become a specialty business. It's not the old spinner racks. When I was a kid, I'd ride my bike to the store, and go through the spinner rack, look for the latest issue. Now, you've got to go to a comic book store and do that, and they're awfully expensive.

The movies have certainly saved them. The movies are probably the next big significant event after the direct market that gave comic books another shot in the arm. When comic books are selling for three, four bucks a piece, that's a little iffy. They've gotten to be very expensive entertainment.

Graphic novels, though, have also helped, having comic books become books, and getting them into bookstores, which, of course, are frequented by entire families.

It did a lot, the direct market. I don't know if it kept the business alive, but it exponentially grew the business. The comic book companies were well aware of that. They wined and dined the distributors back in the '80s. When I was a distributor, they'd take us to Barbados and Florida. We'd have sales conferences. They'd fly us there, and sell us all their new product, and everything. That's changed quite a bit now. Of course, with Marvel and DC not even distributing through Diamond.

That competition was really healthy. It was a lot healthier when there was 15, 16 distributors with warehouses in all these different cities hand-selling to comic book shops. Now, it's not quite as good as it could be, but it's getting along. The comic book shops have adapted. They carry other things besides comics. That was always a real key to the success of the business, to broaden their horizons.

Since Phil Seuling, of course, passed away a while ago, and there are a lot of other key figures from the early days of the direct market that have passed away, I'm trying to think of who... Of course, Steve Geppi is still around. You're still around. Milton Griepp is still around. When we think about who the key people are, you're one of those names that always comes up. It's like if we're going to have a Mount Rushmore for the direct market, Phil's on there. I would say Jonni should be on. Jonni Levas should be on there, too. You should be on there. I don't know. Mount Rushmore is just four. We probably need more than four. How do you feel?

[laughs] Mount Rushmore. That’s good.

How do you feel that when we talk about this, that you're talked about in the same breath as Phil? Of course, Phil was someone you looked up to so much. Is that fair? Do you think, "Oh no. Phil was a much bigger deal than me? How does it feel to be talked about like that?

It was interesting. Milton's article in ICv2, it actually gave me a slightly different perspective on it (see “Bud Plant Deserves”). Because I've been living this whole thing, so I don't sit back and think about the last 50 years. I'm concentrating day to day on getting things done.

It really was a good point that Phil and I represented different parts of the direct market, but yeah, I don't mind being mentioned in the same breath as Phil. Who knows what would happen with Phil if he had lived to a ripe old age. Phil had a kind of a limited period of really high influence, tremendous influence.

I've had a much longer period and, yeah, Milton had a point. I was the one‑stop shop for a lot of material. Fans that live where there's not a comic bookshop or they're overseas where there might not be a comic bookshop, they could come to me and buy material.

I run into those guys all the time at shows and they go, "I've been dealing with you since, such and such a time and I still have those comics I used to buy and, it's been a pleasure to work with you." And so on. I get a certain amount of that. So I can sit back and go, "Yeah, I've played a fairly important role in the comics industry in my own little way. I think that works. I don't mind being on the same level as Phil. I love the guy. He was an incredible guy. If it wasn't for Phil, I don't know. Would I have been doing this? Maybe, maybe not. I don't know. Probably, but maybe not as well. I don't know. Phil, he really helped to educate me working with him. Hard to say. Just like if I had sold out to Capital, would that have made a major difference? Would Diamond be the one distributor left standing today? I don't know. There's no going back and speculating on that. It's a done deal.

Thank you so much. This has been great. Great speaking with you again.

Oh, it's great talking with you, Dan. I enjoyed it.

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

Rapid Growth in the 80s, Selling Out to Diamond, and the Meaning of it All

Posted by Dan Gearino on May 26, 2023 @ 6:17 am CT

MORE COMICS

Also: Longtime Eisner Awards Administrator Jackie Estrada to Retire

July 26, 2025

Jackie Estrada, who has been running the awards since 1990, is stepping down.

Second Win for Akira Comics

July 26, 2025

Akira Comics previously won the award in 2012.

MORE NEWS

Shop Talk, July 2025

July 25, 2025

All this and more in this month's edition of Shop Talk, our roundup of retailer news.

Supplementary Booster Set for the Guardian Class

July 25, 2025

Legend Story Studios will release Mastery Pack Guardian, a supplementary booster set for Flesh and Blood TCG, into retail.