I Think I Can Manage is a weekly column by retailer Steven Bates, who runs Bookery Fantasy, a million dollar retail operation in Fairborn, Ohio. This week Bates takes another look at the relationship between comics and film:

With Batman Begins strong-arming the box office competition and the much-anticipated Fantastic Four looming, I thought it was time to re-examine the relationship between four-color fiction and film. Back in February, I explored the possibility that comic book movies -- a very hot trend these days, in case you've been in a coma -- provided ample opportunities for both profit and loss for specialty store retailers. There's the merchandise, of course: the original source material like comic books and graphic novels, by and large never-before-seen by fans of the films; spin-offs like toys, tee-shirts, and trading cards; and peripheral products like magazines, book adaptations, soundtracks, and DVDs. Savvy retailers will make movie premieres a showcase for their stores and swag by co-oping with theaters, passing out promotional material and coupons, luring comic book movie converts into their places of business. But there's also a darker side to Hollywood hits based on four-color fantasies. Oftentimes, retailers place too much faith (and their financial fates) in a film's future, over-ordering action figures, adaptations, and other ancillaries. If the feature flops, or the distribution is delayed on the merchandise, retailers may find themselves sitting on a pile on unwanted, unsold, and unsalable flotsam.

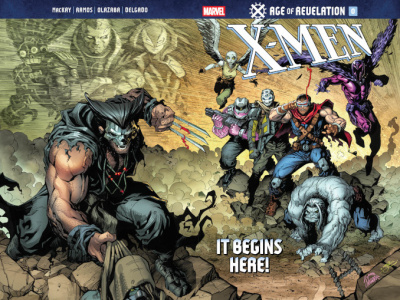

But there's a more nefarious aspect of comic book movies to be examined. At their best, like Richard Donner's Superman, Tim Burton's Batman, Sam Raimi's two Spider-Man films, and Bryan Singer's X-Men movies, comics-to-film adaptations capture the spirit of the originals, bringing to life the toils and tribulations of heroes beyond human ken, struggling to find a place in a world that equally needs and fears them. It's the stuff of legend, translated from flat, four-color newsprint to vibrant Technicolor celluloid. What was previously left to our imaginations -- flight, optic blasts, web-shooting acrobatics, slashing claws, and super-speed heroics -- is projected on-screen larger-than-life, accompanied by a hard-hitting score and state-of-the-art special effects.

And therein lies the rub.

People ask me all the time if a new movie, based on a comic book character or series, brings in new customers to the hobby. While we sometimes see a blip in interest following a movie (Ghost World, Blade, Spawn, Hellboy, and Constantine all come to mind), I would be hesitant to call these curious dabblers in comics 'converts' or 'regular customers.' Sometimes it sticks, but often the paper counterparts pale in comparison to the big screen versions. Ignoring low budget and/or blatantly bad movies, like Man-Thing, Catwoman, and Mystery Men, movies are now capable of doing everything comic books could, only seemingly better. Where we once relied on comics for that magical combination of myth-making characterization and muscle-bound choreography, now we turn to movies for the same emotional and seismic impact. For that matter, as one comic book writer told me, we can get both the soap opera AND the bombastic battles every week on WWE, so why read about 'em?

Is it possible that Hollywood is cannibalizing the comic book industry? Are movies like Sin City and Batman Begins ruining it for readers? With strong ties to the comic book work of Frank Miller, both films have and are turning filmgoers on to graphic novels like The Dark Knight Returns, Batman: Year One, and the Sin City series (which served as a veritable storyboard for Robert Rodriguez' adaptation). But some fans of the films are finding that the books come up short in comparison, lacking the roller coaster expediency and adrenaline-fueled hyper-intensity of the movies. While comic book fans are digging the nigh-literal translation of their favorite stories to the screen, cinemaphiles are less impressed if and when they track down the originals. The blame lies not with the comics creators; obviously, there was 'gold in them thar hills' to inspire such great movies in the first place. Rather, the problem is with us, the audience.

Over the course of the past few decades, viewers have been conditioned to expect a more visceral, intuitive, sensory-rich film-going experience. Sound and visual special effects, music, editing, lighting, and camera angles, have been evolving, all the while training audiences to react more to overt stimuli than to subtleties of plot, character development, and dialogue. We could blame George Lucas, who certainly has contributed greatly to this experiential shift (as anyone who has seen even a single Star Wars movie could attest). However, it would be unfair to single out one director. As movies strive for more extreme stunts, more explosive effects, more 'bang for your buck,' the stuff of classic cinema (almost all of which arguably started with an idea at their core, not just a bigger spectacle) has largely evaporated, save for a handful of films served up for Oscar and the Hollywood elite.

Ironically, while comic book movies (and TV series like Smallville) have been competing with the very comic books which sired or inspired them, the comics industry has been 'fighting back' by bringing in Hollywood heavyweights like J. Michael Straczynski, Jeph Loeb, Geoff Johns, Reginald Hudlin, Joss Whedon, and Mark Verheidan (who has gone full circle from comics to film to comics again), among others. Bringing their cinematic sensibilities to sequential art storytelling, these writers are infusing comics with the very thing that used to make movies great -- characterization-rich stories with complex plots and high drama. Books like Amazing Spider-Man, JSA, Flash, Black Panther, Superman/Batman, Astonishing X-Men, and Green Lantern, are scoring big with comic book regulars. Even the sporadic releases of Clerks creator Kevin Smith still outsell most comics by more traditional, comics-trained writers.